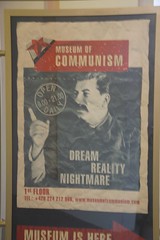

The highlight of my visit so far from a cultural perspective has been the Prague Museum of Communism. The museum chronicles the rise of communism more generally, then specifically in the Czech Republic—formerly Czechoslovakia – focusing on the oppression and harsh political conditions under which people lived during Soviet Rule and highlighting the Czech resistance. From the Prague Spring where the Prague resistance was squashed early on to the Charter 77 group in 1977 and the Velvet Revolution in 1989, the museum goes through the key moments of communism for the Czechs. Through the Czech case I saw some of what the Soviet Union was like—for a country that lived the years under communism as an occupation, as oppression from outside powers.

Part of the museum was a room where you sat and watched a video that included footage of many important moments in the Czech Republic’s history with communism. Most strking was the footage of the Velvet Revolution, seeing young people filling the town square and protesting the regime despite the dangers still posed by the totalitarian government. People had so much courage, were so brave to stand up against this totalitarian government that had police who worked for the state regime, not for the people. Most striking were images of plainclothes policemen beating people -young students- in the middle of the street. Seeing the images brought home how the system pitted one Czech against another.

Today we, that is we Americans, we comfortable young Westerners, know little about this kind of rebellion. It has not been necessary for us. We live in the lap of luxury in so many ways compared with previous generations. Yet turbulent political times, totalitarian regimes exist in other countries, as bad or worse as what I saw depicted here, though not on the same scale as the USSR. We do not live the turbulence in other countries, seldom feel the struggle for realizing ideals of freedom that I felt today as I took in this museum. I found myself thinking that the Soviet Union should be considered a part of us, of my country’s history, because we were in direct opposition to it—became stronger by racing with it, even as it’s leaders led it towards further strength by building on an opposition to us and repressing its people along the way.

The propaganda was astounding—pure lies about what was going on in other parts of the world. Of course they’re lies for me as an American who claims to know some of history, yet were there people who really believed these things? The museum also had posters of anti American sentiments of the time—pure statements about the corrupt capitalist government we had and the pernicious intentions we had with respect to the Soviet Union. I wished I could read the Czech words on many of them as not all had translations.

The Soviet Union was so large, so powerful, so completely invasive of peoples’ personal lives and beliefs. A complete usurpation of the freedom of the common person, under the guise of freeing them from all need and want by freeing them from the need to seek personal wealth. No reward for individual effort, except in the interests of the collective. The ideal was the common man who worked hard—the miner was a hero, the worker who worked harder than he was expected to and accomplished more. Posters from the time depicted a glorification of the plight of the common working man, and in some cases woman, making the worker the hero.

Seeing this museum was deeply impacting to me. I feel the depth of responsibility for being a part of history. My country was a part of the oppression and brutality of this regime. By opposing in the way we did we fueled each other, strengthened each other, made it easier for each other to exist. There was a lot of video footage of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, and during the video they played a song with subtitles—a folksy-sounding Czech singer who I assume was from the time. Accompanying images of the police beating university age kids, the singer wailed “thank you for the pain, which teaches me to ask questions…†thank you for such things as failure and all the difficult things they faced. The song speaks to the hardship of the times, saying thank you, speaking to the effect that hardship can have on the reflective artist—make them live more deeply the current times and express it for others of us to see. I found myself thinking about how easy for the privileged, for us, for the West to ignore oppression today. Around the world people suffer as much or more than the Czechs suffered under communism. But it is almost as if having it on TV all the time, so ubiquitous a part of public rhetoric, makes it easier not to enter into the personal reality of what it is. It makes me ashamed—I’ll go on with my life, remember what I saw, but not take action. What would I do if I lived in a time that depicted in this museum? If I were from Prague and born in 1930 or 1940? Or born in 1970—would I go out and protest in 1989. Would I accept things as they were? Would I stand up for the ideals I think I believe in? Will I stand up, dedicate a part of my life to fighting to reduce suffering and oppression? Will you?

The folksy sounding singer’s name seems to be Karel Kryl, described here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karel_Kryl

and the song he was singing would be ‘DÄ›kuji’ or ‘thank you’.

I visited the museum too, saw the video, heard the song, and on my return home (UK) searched and found his name.

Have fun. I haven’t yet found any CDs of his for sale yet, but I’ve thus far only searched amazon.co.uk and froogle.